I did my first editing on my first short film, Porn Maker to the World, at Simon Fraser University film workshop in about 1967, and got my first hint about how to approach it from a fellow student, Peter Bryant, who introduced me to cutting for the action. Editing is where the visual story is created. Editing actually makes the movie, and is as important, if not more important, than the writing and acting and even directing.

Some of the most famous directors, like David Lean [Lawrence of Arabia], came from editing. But there is a flip side to this. We used to talk disparagingly about an “editor’s film”. An editor working someplace like the National Film Board or on a series would beg and plead to be given their chance to direct. The result was, all too often, a finished product that flowed like melted butter, with every cut perfect, sliding unnoticed past the viewer. Very impressive. Sadly boring.

A good editor can make a good film out of next to nothing. At the same time, an insensitive editor can destroy the best directing, acting, and story. I’ve seen it happen. I remember being a crew member on one film in particular. We were all really impressed with the dailies, the raw film straight from the camera. Man alive, this is going to be a great movie. But by the time the editor got done with it we all looked at each other and asked, what happened to the story?

Have you heard about Eisenstein. He was a famous Russian film maker in the very beginning days of silent movies, back when most movies were shot like a play and nobody even knew about close ups. Eisenstein took a shot of an actor’s face, then intercut it with evocative images- a mother holding a baby, a man pointing a gun at the camera. The actor’s face never changed, because it was all one shot. Yet critics raved about the subtlety of his performance. That is the power of editing. The audience reads in emotions they expect to see. That’s a great lesson for directors, and for actors.

When I was getting started, editing was labour intensive, even painful. That first film, Porn Maker to the World, was shot on black and white reversal stock, processed at the university, and hung to dry under the theater stairs. I cut the original film by scraping off the emulsion on one side and gluing it together with a hot splicer. No workprint. I lost a frame any time I decided a cut needed to be changed and tried to put it back together.

Cranking a workprint, once I started working with workprints, with five tracks of perforated magnetic sound through a synchronizer was heavy work, especially when you made the big leap from working in sixteen millimeter to working in thirty five. That was always seen as getting into the big time.

A bigger problem was in judging how long a credit needed to be on the screen when all I had to go by was a grease pencil line on the workprint. But I’ve already talked about the difficulties with editing in the old days, back when I did the post about getting started and making “Granny’s Quilts”. The point is, I’m past that now. Now I’m in love with digital editing.

It’s probably obvious to my readers, but digital editing changed everything. Suddenly you could experiment as an editor. You can make fast cuts, save a version of what you’ve done. Go back to the previous version, and without taking the tape off the work print and reassembling it. The old rule of measuring by the nose went out the window.

Okay, that probably needs an explanation. One of the first master editors I worked with, as an assistant, was a man called Luke Bennett. Luke had started out airbrushing the sound cuts in the days when sound was recorded on optical stock and the cuts needed to be air brushed to stop them from popping. He told me that one of his mentors would pontificate about editing: “If it’s not a great shot but I need it to tell the story, I use a piece from the end of my nose to the tip of my baby finger. If it’s a good shot, I use a piece from the tip of my nose to my elbow. And if it’s a great shot, I use a piece as long as my arm. That’s what editing is, my boy, it’s measured by the nose.”

I loved editing back when we used actual film. But I love it even more now that we use computers and digital video. I cut our feature length romcom, “Passion“, on Final Cut Pro, an Apple product. And I loved it. The things I could do with that editing program, the ease of making mats and superimpossitions and laying on animated titles in colour… It was like handing me the keys to daddy’s Ferrari*, freedom from constraints, and freedom from the manual labour. I could be creative.

But I haven’t had Final Cut Pro since I burned out my Mac by running it on 240v in China without flipping the switch. And I’m not a major fan of Apple computers, so I’m not buying a Mac.

The last video editing I did was on an ancient laptop with Windows7 running Adobe Premier Pro, and I hated it. It seemed totally lacking in the intuitive controls that Final Cut Pro gave me, the ability to quickly and easily change the size of the frame for example. It’s possible that I just never learned to use it, but…. I managed to muddle through. It’s no wonder that FCP set the standard for computer editing, to the point where a program that can edit on a PC is marketed as a Final Cut Pro emulator.

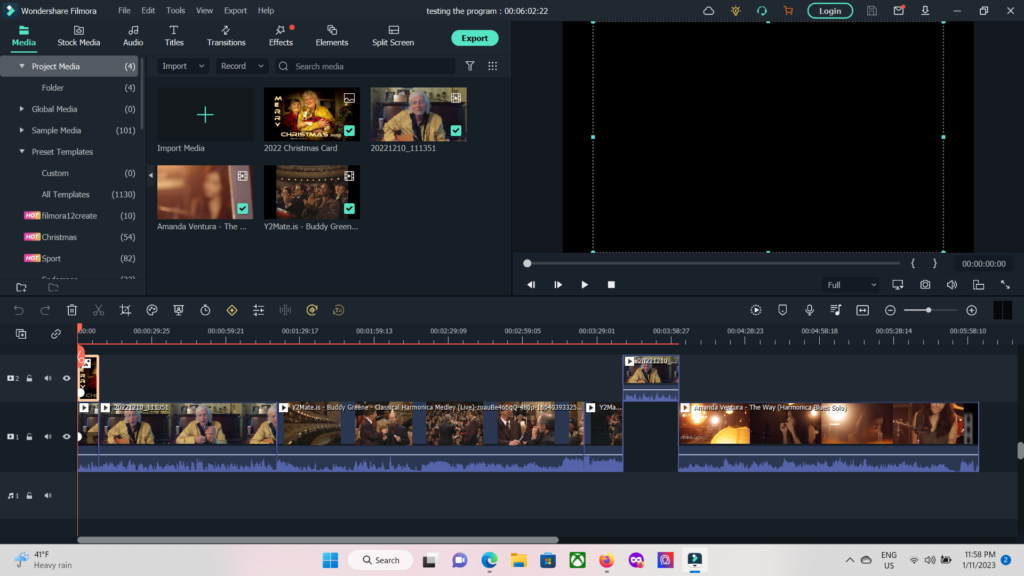

Here’s the thing: Ruth bought me a new computer for Christmas. Now that I have it, with a great graphics card, 16 gigs of RAM and terabytes of storage, I’ve been investigating those Final Cut Pro emulators for Window and I think I’ve found a winner in Wondershare Filmora 11. And the good news is that I could buy a perpetual license, instead of a monthly or yearly subscription.

Now all I need is a project to edit. I have a head full of ideas. Stay tuned.

-30-

*No, my father didn’t have a Ferrari. He would have been embarrassed to be seen driving one. He was a Chevy guy. Driving a solidly middle class car was essential to his image.